As I write this, I am watching the tragic news of the second mass shooting in a week.

While we await more news of the circumstances of this massacre, it is of course the first mass shooting that included several Asian women in Atlanta that is prompting this guest blog. Over the past week there have been times when I have felt seen and noticed, the warmth of being asked how I am doing, and from hearing the words, “I am standing with you.” And on the other, there are moments when floodgates of grief have been released, when I don’t even have the words to adequately or eloquently speak what I feel. If you’ll bear with me, I’d love to share with you some of the experiences that come to mind.

In the past year,

Along with many others, I asked people to stop using the words “China virus” or “Kung Flu” and was mocked as being too sensitive, that it was merely a fact or statement of origin that did not perpetuate racism. I reported to Facebook a post that said all Chinese people should die, stating that we all eat dogs and are clearly evil. The official response was that I needed to distinguish between words I didn’t “like” and “hate speech.” If saying a whole group of people should die is not hate speech, I don’t know what is. I wish that was the only time I read such words, but of course after that, I never reported them again. Because to report something and be told it’s just words I don’t like was almost as painful as hearing the words themselves.

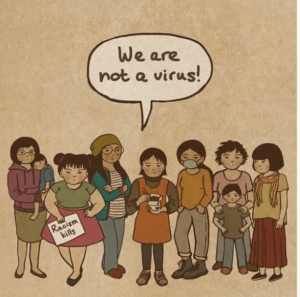

Art by Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom/정 울 림

I watched elderly people who reminded me of my grandparents but who are in fact the ages of my parents be pushed and punched and beaten, and wished those images had been enough to prompt a universal call to action. So I was quite grief stricken when it felt like a mass murder was what it took to be noticed. Then over last weekend, it seemed like all the Asian reporters from every corner of the country were called forward, as if all the affiliate news stations in the country had been emailed to ask if they had any Asian reporters to put on air about this story. It felt complicated to say I felt a bit resentful while also grateful the AAPI community was getting some genuine attention.

Beyond the times this year though,

It’s like my entire life is flashing before my eyes: my embarrassment about my heritage throughout my childhood, the time I shared in a Skid Row School that I might never forgive myself for the ways I didn’t defend my father against racist things people said to him, being called a “banana” and being proud of it, the contrast of feeling not attractive at all as a child and then suddenly being fetishized from my late teens through adulthood.

I have asked myself if I perpetuated the fetishizing of Asian women in the times I was cast in film and tv shows as a Japanese geisha, a Vietnamese “bar girl” during the Vietnam war, as a double for a sushi girl at a restaurant where sushi was served on her body, and a patron at a club in Shanghai. I reflected that perhaps even I did not know that sexual attraction did not equal “not racist.” And remembered the time when an adoptive family I met who had two pre-teen girls from China confessed that they had joined a country club where their girls were not only not welcome, but they hid their existence. Adopting kids from a certain race I learned definitely does not equal anti-racist.

Around this time last year during the George Floyd protests, I wrestled with my privilege. I couldn’t recall a time I had ever worried about my safety when seeing a police officer. Among so many other things the BIPOC community had to contend with, it was clearly not the time to complain about what I was experiencing as it related to the things I “didn’t like.”

Now I am both relieved to no longer be invisible yet also afraid of the visibility. Just this morning, a medical professional posted that as he was getting his children out of the car, a random person yelled, “Thanks for the virus!” This was someone who was just coming from putting vaccinations in arms, who was putting himself and his family at risk for over a year treating those dying from the virus. I fear that now the attention is focused more on the AAPI community that instead of protecting us, it will hurt us more.

I have some hopes.

I hope that this moment will help us see each other more, including those of us within the Asian community. I’ve actually never been in an Asian owned spa. I’ve been to others though and I can tell you not one ever had a note on the door that had to state, “No sex.”

I also wish that more people in this country knew not just the history of Japanese internment camps, but knew about other immigration experiences of the AAPI community. I didn’t learn about the Chinese Exclusion Act until my 20s, which remains the only law ever in this country to prevent a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to this country. Just today I learned about the Rock Springs massacre which killed 28 Chinese miners and burned 78 Chinese homes. And the Hells Canyon massacre where 34 Chinese gold miners where ambushed and murdered.

Finally, I have one request.

That during a time of grieving of many Americans with Asian origins from 48 different countries (operative word Americans), it feels pretty disrespectful to say, “sorry you’re sad, but China is…” One day it would be nice not to be seen as perpetual foreigners and viewed as a monolithic group that may never belong. Nothing would mean more to me at this time than starting with engaging in the conversation and learning our histories here in North America.

In service and solidarity,

– Selena

p.s. If you’d like to join us for an informal conversation about #stopasianhate and sharing our learning, our Billions Institute team will be on Clubhouse next Thursday April 1st at 11amPT

p.p.s. Recommended reading: The Chinese in America by Iris Chang

In an epic story that spans 150 years and continues to the present day, Iris Chang tells of a people’s search for a better life—the determination of the Chinese to forge an identity and a destiny in a strange land and, often against great obstacles, to find success. She chronicles the many accomplishments in America of Chinese immigrants and their descendents: building the infrastructure of their adopted country, fighting racist and exclusionary laws, walking the racial tightrope between black and white, contributing to major scientific and technological advances, expanding the literary canon, and influencing the way we think about racial and ethnic groups. Interweaving political, social, economic, and cultural history, as well as the stories of individuals, Chang offers a bracing view not only of what it means to be Chinese American, but also of what it is to be American.